Arch Patton

DOWN IN THE VALLEY

Chapter 11

By James Strauss

Arch and Matisse hiked the quarter mile back past Sunset Beach until they came to Ted’s Bakery. Ted Nakamura ran the place and he knew Matisse from way back, or so Matisse claimed. Ted wasn’t there when they arrived and the place was packed. Some tourists, but mostly local surfers and other semi-rejects hung about inside the single small room or sprawled at rusting metal tables on the outside. Ted had expanded the outdoor eating to the other side of the parking lot, but no one ever went to sit at those tables, even just to wait for their orders. Arch read a sign on the cash register that said the credit card machine was broken. Matisse informed him that the machine had been broken since the nineties.

“You got cash?” Matisse whispered, between flirting exchanges he was making with the tired and beaten-looking women behind the counter.

“No, all I’ve got is my card,” Arch responded, not really caring because he wasn’t hungry anyway. The encounter at the beach house had involved running down the beach before Kurt and Lorrie could figure out they were there. Just one more element of demeaning abuse he’d suffered since arriving on Oahu only days earlier.

“No problem bra, they got ATM,” Matisse stuck out his hand.

Arch saw the ATM in the corner, sitting up next to a coffee machine, both looked barely functional. Cups sat next to the coffee machine, so he poured himself one before stepping in front of the ATM. “Seven dollars?” he hissed at the screen. He had no choice. The card was good for at least a hundred more dollars because bills started slipping one by one into a slot near Arch’s right knee. Arch counted the money before realizing the old food-stained robot hadn’t spit his card back out. He whacked the machine loudly with the flat palm side of his one good hand.

“Hey,” Matisse interrupted. “This my friend,” he said, pushing Arch aside. He put both his plate-sized hands against the sides of the machine and then leaned forward. He blew into the thin dirty slot Arch had put his card into. The machine gurgled with seeming glee before noisly spitting Arch’s card out. Matisse put the card in his pocket, but Arch was right there with one hand extended when Matisse turned back to the counter to order.

“Are these more of the friends you don’t have?” Arch asked, putting the card carefully into his wallet. “I’ll be across the tarmac in the other area,” he said, handing over two twenties to Matisse. “I’m not hungry. But get whatever you need.”

After only a few minutes, Matisse joined him at one of the empty tables. “They come get me. You got teri-plate with double mac and white rice. Give you energy. This best loco moco on windward side.” Matisse put the remaining twenty on the table in front of Arch, sensing his dark mood.

Ted’s Bakery Teri Plate Beef and Pork with Mac and Rice

“What now, bra?” Matisse asked.

“What now?” Arch questioned, looking up at the blowing palm reeds not far overhead. He looked back down. Only a few feet away distant cars sped past on Kam Highway, while an old oriental man wearing only one rubber “go-ahead” slipper tried to work his arm down into a rusty container containing used soft drink cans. For some reason chicken wire mesh had been placed over the top of the can. This allowed the man’s arm to reach in and grab cans, but wouldn’t let him pull his arm back out with a can still in it. The old man continued to struggle without sound or comment, but couldn’t seem to extricate his arm, and wouldn’t let go of a can to help himself.

“Christ!” Arch said, his voice an exasperated hiss. He got up and walked over to the struggling man. With one foot he struck the side of the old oil barrel with all his strength. As both the barrel and the old man fell to the ground, the top broke loose from the impact. The old man sat up and worked his arm slowly back out of the mesh, and then began collecting the cans that spewed forth. Without acknowledging Arch in any way, he placed several cans carefully into his old backpack, slung it over his shoulder, and then walked carefully away on the very edge of the road, his one thong making a smacking sound every time it hit the asphalt.

Arch watched the bent old man re-adjust his load from time to time until he disappeared. He made his way back to Matisse’s side, but stopped just before he got there.

“That’s it,” he said, his expression changing from wrinkled depression to smiling delight. “We kick the stupid can. We’ve been caught, beaten, tortured, abused and then caught again. But we’ve got a gun, and guns are something I’m really good at. Let’s go kick the can and see what comes rolling out.”

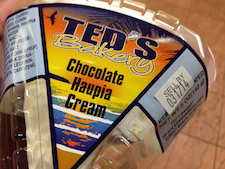

One of the used-up looking women from the bakery appeared, her arms laden with paper plates. Arch sat next to Matisse, trying to curb his new enthusiasm. All of a sudden the teri-plate the woman set down in front of him looked delightful, as did the plate set in front of Matisse. After unloading a small bag of condiments and plastic silverware, the woman removed her last package. It was obviously a pie box. When she put the box down she said “Chocolate Hupia Pie from Ted,” and departed.

One of the used-up looking women from the bakery appeared, her arms laden with paper plates. Arch sat next to Matisse, trying to curb his new enthusiasm. All of a sudden the teri-plate the woman set down in front of him looked delightful, as did the plate set in front of Matisse. After unloading a small bag of condiments and plastic silverware, the woman removed her last package. It was obviously a pie box. When she put the box down she said “Chocolate Hupia Pie from Ted,” and departed.

Arch took one bite of the macaroni salad and then proceeded to eat both scoops without stopping. The macaroni salad at Ted’s was legendary and it was obvious why. He watched Matisse go to work on his huge Loco Moco. Prime rib gravy flowed down the sides of his mouth, as he downed half the giant burger patty laying atop three fried eggs and a mound of sticky white rice the gravy flowed around. When Arch was done with his teri-plate he walked over to the bakery’s main building and used the bathroom. On his way back he thought about the pie and what the word Haupia might mean. Matisse sat contentedly back in his seat waiting for him, sipping from a can of Guava soda.

“How’s the pie?” Arch asked leaning down to open the box.

“Oh,” was all Matisse said, just before Arch saw that the box was empty.

“The whole pie?” Arch asked. “You ate the whole damned pie? Nobody can eat a whole pie in only a few seconds.”

“Ah, maybe you were gone longer than you thought,” Matisse answered, getting up to put their used plates into a nearby trashcan.

“You gotta have some of that Haupia pie soon bra,” he murmured when he came back.

They walked together back to where the Pontiac was parked. Arch thought it was appropriate that no other vehicle ever seemed to park very close to the bizarre looking car. “What’s haupia mean?” He asked Matisse, who was gingerly leaning against the Bonneville’s hood.

“Coconut,” Matisse responded. “Coconut cream, if you mean in Ted’s pie.” He looked over at Arch. “What’s next?”

“You don’t have to come,” Arch said. “I’m taking the gun and going right back at them through the double door. Somebody’s likely to get shot, and probably I’ll be that person. You can wait here and see what happens. I’m done being a punching bag for this outfit. They’re up to their necks in something that’s dark and deadly dangerous to a lot of people. And I’m not quitting until I know what it is.”

“Why?” Matisse asked. They were both silent for a moment, watching tourists gather to go down into the knee-high waves below. “You retired. Why go on? You can go fishing or travel or do something else with your life.”

“Like what?” Arch shot back, instantly. I’ve traveled. I don’t like fishing. You and Virginia are about the only friends I’ve been able to make. I’m not doing very well with her and I’ve only known you for how many days?”

“Okay, but going in there and shooting everyone if they don’t, won’t or can’t talk seems dumb. Ahi does have some guys. Why don’t we go back and see him. Maybe if a bunch of the people show up with us nobody has to get shot. The people were up against aren’t like that drunk getting old soda cans out of the trash.”

“So, you’re not coming with me?” Arch said.

“No, I’ll go,” Matisse answered immediately. After a few seconds he added: “I just think we should talk to Ahi first. He’s been on this side of Oahu longer than we’ve been alive. Maybe he knows something that can help. If we shoot those men, or even Virginia, they’ll lock us up at Halawa for a lot of years.”

“I’m not going to shoot Virginia,” Arch said. His tone was softer, his words coming out slower and more contemplative.

“Not on purpose. Once shooting starts though, anything can happen,” Matisse said.

Arch looked over at his newfound friend in surprise. The rough -talking, hard-eating islander was taking an unexpected tack. “We’ve got time. Okay, it’s only half an hour back, but my mind’s pretty much made up.”

“Nah,” Matisse replied, pointing back the way they’d driven in from.

“Ahi at Kahuku this hour on Sunday. His wife works shift at Kahuku Hospital only seven miles. Five minutes, maybe less without traffic.”

The ridiculous Pontiac, which hadn’t had an oil change for God knew how many miles, turned over and started instantly with a gutty roar. Matisse always pumped the accelerator for half a minute before turning on the ignition, no matter how many times Arch told him he was flooding the carburetor. Matisse drove the seven miles at his usual dangerous clip, passing cars in no passing zones and waving at almost all pick up trucks they came across, moving or stopped. It didn’t seem to matter if anyone was in the parked trucks, Arch noted.

Matisse parked in a doctor’s parking spot at the very front of the hospital. They got out and went inside the emergency entrance. Matisse seemed to know every nook and cranny of the place as they made their way through the labyrinth of the complex. He said “hey” to everyone they passed, or simply made the Shaka symbol, which involved extending the index and little fingers of his right hand while wiggling his wrist. They found Ahi holding court at the back corner of the cafeteria, once more surrounded by a group of local people sitting instead of kneeling. Matisse stopped Arch from approaching by putting out his meaty left hand and hitting him on the chest.

Matisse parked in a doctor’s parking spot at the very front of the hospital. They got out and went inside the emergency entrance. Matisse seemed to know every nook and cranny of the place as they made their way through the labyrinth of the complex. He said “hey” to everyone they passed, or simply made the Shaka symbol, which involved extending the index and little fingers of his right hand while wiggling his wrist. They found Ahi holding court at the back corner of the cafeteria, once more surrounded by a group of local people sitting instead of kneeling. Matisse stopped Arch from approaching by putting out his meaty left hand and hitting him on the chest.

“He’s talking story,” Matisse observed. “We wait for break. He’s seen us so it’ll only be a little bit. Let’s have some fried chicken. It’s great here. Coffee over there. Molokai Peaberry. Da best. Free. Two bucks really, but nobody ever says anything if you don’t pay.”

Arch got a cup of coffee and gave his card to the cashier, indicating that she should put Matisse’s heaping plate of chicken on the bill. The woman smiled a big smile and put the questionable card on the lip of her register.

Matisse joined him a few minutes later. “Signed for the stuff, hope that’s okay,” he said, plopping Arch’s card on the table between them.

He began working his way through the chicken, pushing a drumstick over in front of Arch. Arch looked down at the overly blackened thing but took a single bite anyway. Like almost all food cooked by locals in Hawaii, it was unbelievably delicious. He took small bites until only the bone was left. Ahi stood, as Arch was finishing, and wading through his little group of followers, and made his way ponderously to their table.

“Permission to sit?” he asked, unexpectedly.

“Sure,” Arch said, puzzled by the man’s strange use of words

Ahi smiled broadly. “I was a Marine, so many years back.” He turned the end chair around and sat down on it, cradling his huge forearms over the back.

Arch didn’t know what to say, he was so surprised.

“You got trouble because the meeting at the house didn’t go so well?” the big Hawaiian asked.

“No,” Arch answered, truthfully. “It didn’t go at all. Virginia might be there or she may not. The guy who did this to my hand was there, with his partner, both armed. I wanted to go in but Matisse said we needed to talk to you first. So here we are.”

“The Marine Corps’ frontal assault’ not always bad, but usually only works with a lot of casualties.” Ahi said the words with a smile, his dark eyes seeming to twinkle.

“Yeah, that’s what Matisse said,” Arch replied, glancing over at Matisse who was working his way through an entire fried chicken not long after consuming a monster breakfast and a whole pie. “What do you think?” Arch asked, finally.

“They got a big plane at Bellows,” Ahi said. “Landed in the night some time back. Lots of wind from that plane. What’s on it is important. Somehow it’s connected very deeply with something in the mountains here. And this is my land, my people’s land.”

Arch was surprised again. It had taken Arch days to find out the same information, and not nearly in as much detail as Ahi had.

“There’s a woman named Virginia in charge of the operation, only not really,” Arch said. “General DeWare from Kaneohe seems to be her boss, although I’m not sure of anything there. She’s at that house on Sunset. I need to talk to her about everything, and I can’t do that if she’s guarded by some armed men. Matisse thinks it’s a bad idea to use the frontal assault, so again, here we are. Any suggestions?”

“John Martin,” Ahi said, after almost a full minute of staring up at the foam ceiling of the cafeteria.

“John Martin?” Arch asked, baffled.

“Actually, Sergeant John Martin,” Ahi replied, his eyes coming back down to meet Arch’s own. “He runs the Honolulu P.D. over here. Got put out to pasture years ago for drunk driving. Now he’s the man.”

“Haole man, like me, running the police over here?” Arch asked, in surprise again.

“You not Haole,” Ahi laughed. “You here so long you like one of the people. You Kama’aina. And John has a Haole name, but he actually one of the people. Ohana. Of the land.

Arch accepted the huge compliment with a big smile of his own. The “H” word was almost universally used by locals to describe Caucasians in Hawaii, whether they were born there generations ago or simply visiting as a tourist, and generally they used it right to their faces. “So, what’s Sergeant Martin supposed to be able to do here?”

“John brings a bunch of the guys in uniform,” Ahi said. “What can they do? Shoot the police? Arrest them? I don’t think so. You get Virginia’s attention. Maybe no violence. I’ll come too. I’ve been shot before.”

“Shot before? Marines?” Arch asked.

“The Nam. An Hoa. Sixty-Nine.” Ahi answered, his expression turned deadpan serious.

“You don’t look that old,” Arch said, with doubt in his voice.

“You don’t look like a spy. You don’t look like a tough man. You don’t look like you’re violent. You don’t look lost or like you don’t have a life. You don’t look like you’re old enough either. Some of us have that ability, not to look like what we are or what we should look like from where we’ve been.”

Arch absorbed what the big Hawaiian said without speaking for a moment. Matisse finished his chicken, then licked his fingers clean before using several napkins. Arch thought he detected a vague knowing smile on the man’s lips while he worked.

“John Martin and his merry men it is,” Arch said, finally.

“We go Laie Point?” Matisse asked, getting to his feet.

“I’ll call. Take a few minutes for John to gather his guys together,” Ahi responded. He took out a new iPhone 6 from a hip pocket with some difficulty, before standing and backing away from the table.

Matisse smiled and followed Ahi but only to dump his tray of trash into a nearby bin. He returned to once again sit across from Arch. “See, I told you. What can they do at that house if we show up with a bunch of local cops? Ahi’s the man. My bra.”

“Really? What happens when those clowns inside the house simply fail to come to the door and there we all stand in the driveway?” Arch replied, slowly shaking his head. “They’ll know we know where the house is too.”

Ahi pocketed his phone and walked to the edge of the table. “They’re coming. John was a Marine too. He loves this kind of stuff. I don’t know how many of his buddies are coming but it should be enough.”

They walked back through the convoluted corridors of the hospital until they arrived out by the car. “I’ll put the top down,” Matisse volunteered. Arch wondered if Ahi would fit into the cavernous back seat even with the top down. It took a few minutes, and not a little effort, to get loaded into the car, but then they were on the road. Matisse took the car up to blinding speed, closing fast on some tourist’s rental car in front of them. Ahi leaned forward and briefly gripped Matisse’s shoulder before letting go. Matisse immediately slowed the Pontiac and followed the tourist Toyota all the way back to Sunset Beach. Arch would have thanked Ahi but the passing wind in the convertible was too loud for his voice to he heard.

The turn down onto the access road unexpectedly became dramatic, as they approached the outer gate normally blocking entry to the house. Two unmarked vans and a bunch of privately owned police cars clogged the entire area. The gate to the house and the garage door were gaping open. Several officers were standing at the back of a black Chevy Suburban parked inside the garage. Matisse pulled the Pontiac up close to the back of one of the vans and shut it down. Both men helped Ahi extricate himself from the rear seat. The officers stopped talking and watched them approach.

“Inside,” one uniformed officer said, pointing toward the wall at the back of the garage.

Arch was the first one through the back door. He passed through a short corridor and then into the residence’s ground floor main room. The big double glass door gaped open, as it had before, with the drapes still flapping in the light wind. Virginia sat on a long couch facing him, her eyes hugely round, her mouth sealed shut with a piece of duct tape. Duct tape also held her knees together, and it was obvious that something held her arms together behind her back. A tall, dark and handsome police officer stood next to Virginia’s right shoulder. He was in uncommonly good physical condition without an ounce of fat, much less the usual thick layer most islanders carried around.

“Ahi, uncle!” the officer exclaimed, as Ahi trundled in with Matisse just before him. “You said the woman shouldn’t speak until you got here so this is the only way we could shut her up. The fellas she was with are upstairs, a little less comfortable, but okay. I put their guns in the trash compactor. All you have to do is push the button. We also restrained them with tape so you don’t need keys or any of that. Anything else?”

“You want to know what this is about?” Ahi asked his nephew.

“Nah, uncle, they not very interesting. No drugs, just a lot of talk about how important they are. Call us if you need anything.” Several other officers in SWAT uniforms began to file down the stairs. In seconds the house was nearly empty.

Arch sat next to Virginia on the couch and began to slowly peel the duct tape from her face whispering “I’m so sorry,” as he worked.

Some minor editing suggestions follow:

ATM. “Seven dollars?” he hissed at the screen. He had no choice.

/ I’m assuming the 7 dollars is a transaction fee? /

Only a few feet away distant cars sped past

“away” and “distant” seem redundant or contradictory

Only a few feet away cars sped past

rusty container containing used soft drink cans.

“container containing” words seems too similar

Maybe substitute “receptacle” or “drum” for “container”

rusty receptacle containing used soft drink cans.

OR rusty drum containing used soft drink cans.

“Chocolate Hupia Pie from Ted,”

The picture and later text says “Haupia”

“Chocolate Haupia Pie from Ted,”

/ There are many bakeries in Hawaii that serve this delicious pie so it’s hard to say which bakery made this pie first but I think it is safe to say that it was Ted’s Bakery on North Shore Oahu that made it famous. It is the perfect blend of chocolate, coconut, and cream and it just might be my favorite pie of all time.

https://www.favfamilyrecipes.com/chocolate-haupia-pie-teds-bakery-copycat/

The people were up against

“we’re” instead of “were”

The people we’re up against

Blessings & Be Well DanC